Establishing a precise origin for the Pyrenean Mountain Dog is impossible. What is certain, however, is that the breed is not indigenous to Europe; in fact, its remains are not found in fossil deposits prior to the Bronze Age. The first skeletons of these dogs, together with the horses buried with their harnesses, are found accompanied by bronze objects and were probably introduced into Europe following the Indo-European invasions which spread this metal together with the art of using the horse (Duconte Ch. and Sabouraud J.- A. 1967, Bulletin ACP n°30 – 1999, Cazottes P. 2003).

In the Pyrenees, in the Central Apennines, in the Tatra Mountains, in Bohemia and Hungary, in the Caucasus and as far as the Moroccan Atlas, there are dogs so similar that their common origin from a single stock appears clear: head of the wolf-molossoid type, large size, powerful trunk, totally or predominantly white coat, with thick undercoat and long flat hair. The use is also similar: guarding the flock and the home, and defending them from predatory animals and ill-intentioned animals, in mountainous territories with harsh winters and rough terrain.

The common ancestor of these dogs must be sought in the Tibetan Mastiff, which would have followed its masters from Central Asia during their migration on European soil.

The two main strains of molossers probably descend from this ancient oriental dog: the stockier one, with short hair and a brachy snout, more suitable for combat and for guarding the house and property (Canes Villatices and Canes Pugnatices, ancestors of the current mastiffs ); the other with more harmonious shapes, long hair and a standard muzzle, more suitable for the defense of livestock (Canes Pastorales, ancestors, in general, of the current mountain dogs).

However, the ancestors of the current Pyrenean Mountain Dogs were very different subjects from the type that can be admired today. Their colour, always on a white base, highlighted large reddish and dark gray spots scattered not only on the head but also on the body. The breed that we could define as “prodromal” of the current one would have developed on both sides of the Pyrenees (French and Spanish), showing characteristics common to those breeds that would have developed later: the Pyrenean Mastiff, on the Spanish side of the mountains, and, indeed, the Pyrenean Mountain Dog, on the opposite side.

The political separation of the borders, which took place with the “Treaty of the Pyrenees” of 1659, marked the clear definition between Spain and France. One is led to think that, among the anthropological consequences that the population experienced following the treaty, there was also that of suffering less promiscuity in the grazing of the flocks, with a consequent difference in the selection of dogs dedicated to guardianship. It is probable that the selections that took place on the Spanish side suffered the genetic influence of the Spanish Mastiff, thus drawing on a considerably greater weight, with more markedly molossian traits, but maintaining the white spotted badger coat. On the contrary, on the French side, the dog managed to maintain a surprising purity, characterized by a greater lightness than the Pyrenean Mastiff. In addition to the white coat with patches of wolf gray (badger), probably, as mentioned, the original color of the ancestors of the breed, there was white (by now typical), favored by many shepherds due to its easy identification at night, and white with orange spots.

In its high native valleys, the Pyrenean Mountain Dog, “dressed” in an iron collar bristling with spikes, which saved it from attacks by bears and wolves, had the task of defending the herds and peasant families from attacks by wild animals, stray dogs and marauders.

Many of those who, through the Pyrenean passes, sought a better fate in neighboring Spain, took advantage of the livestock which was very numerous in the uncontrollable pastures on the mountains. The number of these brigands became so high that it was impossible to avoid raids.

There is a document from 1391 by Gaston Phoebus which narrates the visit of King Charles VI to the County of Foix, and gives news of these dogs which helped to save the same king from the attack of a ferocious bull as he reached the Castle of Mazères. From that moment, the lord of Foix decided to entrust the guard of his lands and his manor, which still exists today, to numerous packs of mountain dogs by now well known for their qualities.

In a document of 1407, preserved in the National Library of Paris, it is mentioned that, after Foix, the Castle of Lourdes also adopted the same control system, especially for the night, and special walkways were built for dogs along the tops of all the surrounding walls.

Towards the end of the 14th century, the Patou, still called today after the term “pastre”, i.e. “shepherd” in old French, left many of the mountains to take care of the surveillance of the castles.

In 1675, Madame de Maintenon, morganatic wife of Louis XIV, accompanying the Dauphin in the waters of Barèges, discovered the Pyrenean Mountain Dog. Seduced, she decides to take a specimen with her to Paris. The great white dog became the admiration of the Court of the Sun King, where he received the noble distinction of “royal dog”. It was then introduced as a companion dog, later also appearing on the French royal coat of arms.

During the 19th century there were numerous paintings in which the dog was the protagonist, a sign of its indisputable fame. But the first description will have to wait until 1897, by the Count of Bylandt.

Although all the Pyrenees have been populated by Mountain Dogs, in reality the typical subjects come from an area in the center of the mountain range, and precisely from the pastures that dominate Barèges, Luz, Saint-Sauver, Cauterets; spas known and visited by aristocratic tourists; only area frequented by good society. (Byasson E. 1907).

In 1807 P. Laboulinière insisted on its usefulness in the “Annuaire Statistique du département des Hautes-Pyrénées” (Tarbes. Lavigne): “…The variety of the canine species called Shepherd Dogs is very widespread in the mountains where it is of a truly extraordinary size and strength; this is a variety that bears the name of Dog of the Pyrenees: it is responsible for guarding the flocks which it defends against the attack of wolves and bears which, without it, would soon destroy the only wealth of a whole population of shepherds”.

In 1813 Dralet describes them as follows (“Description des Pyrénées”): “…Our shepherds are extremely helped by sheepfold dogs, remarkable for their enormous size, for the whiteness of their coat and for the volume of their voice. Throughout the night, these animals keep making the echo of their barks echo. What if a wild animal approaches the flock? If he is a wolf, only one dog dares to challenge him; it takes two or three to resist the attacks of the bears…”. (Cockenpot B. 1998, ACP Bulletin n°31 – 1999, Cazottes P. 2003).

However, during the nineteenth century it was the Romantics who really got to know it during their excursions and climbs in those inaccessible places where they often met shepherds and dogs that aroused their enthusiasm. Even painters begin to depict him accompanying a hunter, pounced on a wolf or resting among a group of mountaineers. In these romantic images the dogs are reproduced, broadly speaking, with their current characteristics and also with certain peculiarities such as the double dewclaws on the hind limbs. Taine in the “Voyage aux Eaux des Pyrénées” (1855) portrays them at work with the flock: “… Huge dogs with woolly hair, spotted with white, walk powerfully on the sides growling when someone approaches them … ”.

In the same period many English tourists also went to the Pyrenees to spend their holidays and, on their return, published their stories and their impressions of the country’s curiosities, including dogs: “…They are very ferocious and it is dangerous to meet them in the mountains when they are not accompanied by their master…”. (Harding JB 1830).

They are even included and celebrated in famous novels: in H. de Balzac’s “Modeste Mignon” (1844). Dumay, who is in charge of watching over Modeste’s virtue, has his house guarded by two Pyrenean dogs. In this period they begin to be described not only as fierce guardians, but also for the sweetness of their character. In 1855 the favorite writer of many generations of wealthy children, the Countess de Ségur, wrote the story of Biribi in her book “Les vacances”: “…The dog was two years old; he was large, strong, of the breed of Pyrenean dogs, which fight against the bears of the mountains; he was very sweet with the people of the house and the children, who often played with him, who harnessed him to a small cart, and tormented him with caresses; Biribi had never bitten or struck her fingernails…”.

The curiosity of tourists, the spread of fame and the success of these dogs lead to uncontrolled commercialization which proves to be fatal for their breeding. The inhabitants of the mountain, seen the economic advantage, sell more and more their animals to the bathers, and in those places their number decreases rapidly, while many specimens are exported in most of Europe and in America. In reality, the subjects sold are often of poor purity, and good specimens will arrive only later. (Byasson E. 1907, Duconte Ch. and Sabouraud J.-A. 1967, Bulletin ACP n°5 – 1988, Cockenpot B.1998, Bulletin ACP n°31 – 1999, Bulletin ACP n°32 – 1999, Bulletin ACP n° °35 – 2000, ACP Bulletin n°36 – 2001, Cazottes P. 2003).

In 1868 Oscar Commettant describes the Sunday market that was created in Cauterets where the shepherds come down to the village to sell, no longer dedicating themselves to conserving the breed with the same care as in the past.

Each spa season thus sees a large number of dogs leave; in the stations of Pierrefitte or Argelès they are sent in crates bearing the words: “Give me a drink, please”. The Patous are scattered everywhere and, crossed with other races, they leave ugly mestizos.

However, the decrease in number has at the same time another important cause: the wolves and bears hunted for centuries and poisoned by gamekeepers with strychnine drastically decrease so that the flocks are no longer threatened and the Pyrenean dog, having become useless, is abandoned and almost disappeared from the mountains towards the end of the 19th century. (Byasson E. 1907, Cockenpot B. 1998, ACP Bulletin n°31 – 1999, ACP Bulletin n°35 – 2000, ACP Bulletin n°36 – 2001, Cazottes P. 2003).

For this reason the need is felt to safeguard what little is left of the breed and passionate dog lovers appear who know how to give it a new impetus. The first detailed description of this dog appears in 1897 in the book “Les races de chiens” by Count Henri de Bylandt.

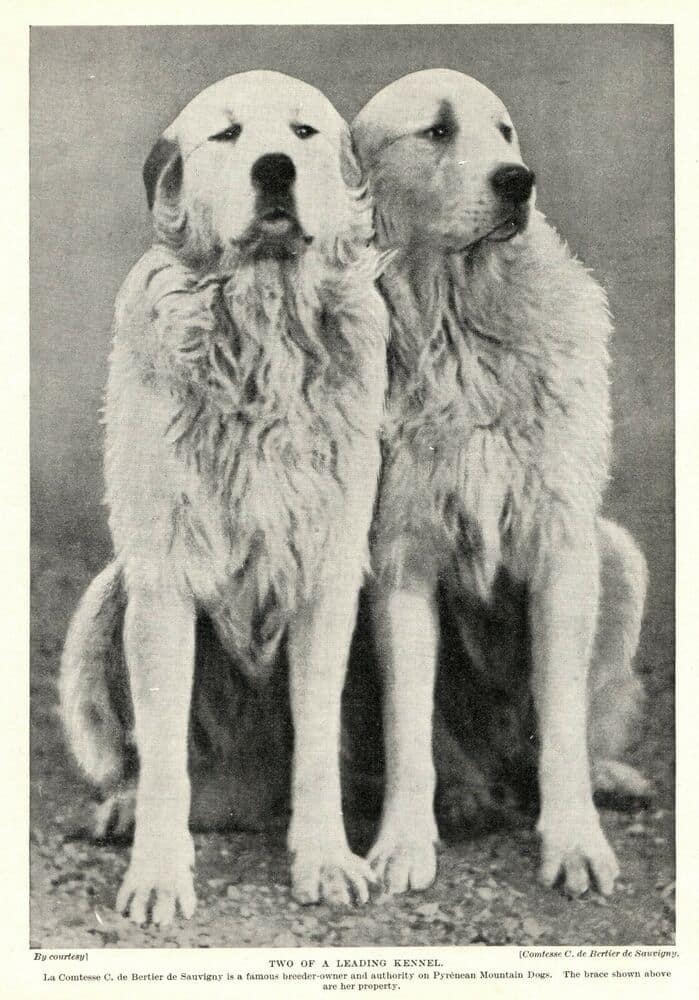

In 1907, Doctor Moulonguet, Monsieur Jean Camajou and Monsieur Bernard Sénac-Lagrange (considered the father of the breed), under the presidency of Baron de la Chevrelière, founded the first breed club in Cauterets called the “Pastor club”, where they the first official standard, then registered in 1923. Meanwhile, Count de Bylandt and Mr. Théodore Dretzen (local breeder, forerunner of modern breeding of the Pyrenean Mountain Dog) undertook a study trip across the Pyrenean chain to verify the consistency and the quality of the surviving specimens and come to the conclusion that only in Argelès-Gazost does there exist a group of purebred dogs. In this locality they founded together with the notary Eugène Byasson (author, in 1907, of the first brochure “Le Chien des Pyrénées” dedicated to the Pyrenean dog and containing its history) the “Club du Chien des Pyrénées” (C.C.P.). While, in 1923, on the initiative of Sénac-Lagrange, the “Réunion des Amateurs de Chiens Pyrénéens” (R.A.C.P.) was born, then affiliated to the Société Centrale Canine and subsequently to the F.C.I. The intent of the club is to maintain and safeguard the breed by favoring the selection of the most representative subjects.

In the meantime, the war of 1914-1918 had disastrous consequences on the entire canine population due to the economic hardships that caused the slaughter of many dogs and the malnutrition of the survivors. Numerous animals are killed in the conflict, as they are used as couriers during war activities. There is a risk of disappearing again, also because many breeders prefer, for reasons of costs, to direct their interests towards smaller sized dogs, more easily feedable.

In 1927 the consistence of the breed was still rather scarce, so much so that Sénac-Lagrange wrote: “…In an era in which fashion is increasingly oriented towards small size dogs, in times in which the qualities of guard dogs and as a defense they find less and less use, it is legitimate to think that, whatever the efforts to make it known and appreciated, the breeding of the Pyrenean dog has little chance of taking a serious diffusion. Outside of its places of origin it will remain in the hands of an elite proud to simply own this magnificent dog and to keep it in its primitive beauty…” .

At this point, the best subjects are chosen by eliminating from the breeding the dogs showing signs of crossing especially with the Mastiff and the Saint Bernard; it seems, in fact, that a stallion of the latter breed had been introduced in the region before the war (Duconte Ch. and Sabouraud J.-A. 1967, Bulletin ACP n°5 – 1988, Cockenpot B. 1998, Bulletin ACP n° 31 – 1999, Cazottes P. 2003).

Today the Pyrenean Mountain Dog is present all over the world more than ever before, also and above all thanks to the media role played by the French television series of 1965, the Japanese animated series of the 80s and the French feature films of the recent years, all having in common the literary subject deriving from the children’s novel by Cécil Aubry, “Belle et Sébastien”.